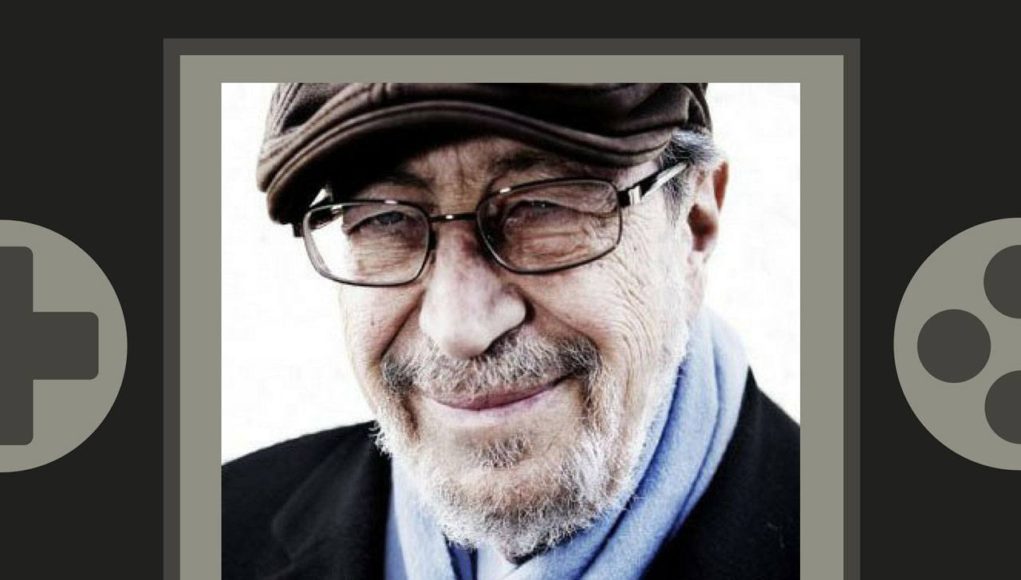

Edgar Schein (USA) was the Society of Sloan Fellows Professor of Management Emeritus and a Professor Emeritus at the MIT Sloan School of Management. He has written extensively on the topics of organizational culture, three levels of culture, culture, and leadership, and organizational culture models to name a few.

This article is from the GuruBook edited by Jonathan Løw.

_____

Edgar Schein about Presence and Wisdom

It is all well and good to be invited to write something as a “guru.” Presumably, that is supposed to mean that with all of your eighty-eight years of experience, you should know something to pass on to younger people.

At the same time, you realize that the older and presumably wiser you are, the less confident you are about wisdom, truth, and knowledge.

Maybe the hardest thing to discover in life is how fragile you are

What is wisdom anyway, more facts, more skills, more caution, more resilience, more agility, and, perhaps most of all, more humility? Maybe the hardest thing to discover in life is how fragile you are, how much of what happens is out of your control, and in fact, how dependent you really are on others.

Presence and Humble Inquiry

As I think about humility I also am reminded of a persistent question, which I could not answer. How come some people clearly have more “presence” than others? How come some people are noticed immediately when they enter a room, while others are not noticed at all?

This question bothered me because I often felt I was not noticed until someone introduced me, gave me a platform, or silenced the room on my behalf. How come some people can do this for themselves, can create their own platform, and be present from the moment they enter a new situation, whether that be a classroom, a party, or even a crowd of strangers?

_____

READ ALSO: How Taking Ownership of your Life will make you a Better Leader and Manager

_____

Personality characteristics like extraversion-introversion, social ascendance, assertiveness, and emotional intelligence did not cut it for me. Those might all play a role, but deep down I felt there was something else in the notion of presence that we had not yet figured out.

An Actor must have Presence

Then one year I was having a conversation with a fellow organization development consultant and brought up this topic because I had learned that this man, let’s call him John, was also a successful part-time actor.

I turned the topic to the question of whether this “presence” issue was important in the craft of acting, to which he replied with some intensity, it is “all important.” An actor must have presence in front of an audience or camera or things will not go well. So naturally, I followed up with the question of “what does it take for an actor to be present?”

A long pause followed. John wondered out loud about the same question and gradually worked out his answer. He said that he was currently in a play where he had a tiny part. He was the butler who had to make an announcement of someone’s arrival.

And it was thinking about this bit part that revealed to him the answer—as he was getting ready to step on the stage and deliver his line, he had to know why he was there.

He, of course, had to know his lines, but, more importantly, he had to know and understand the play, the scene, the importance of the announcement, and the consequences if he fouled up in some way.

___

READ ALSO: Otto Scharmer: The World of Today and Tomorrow

_____

He said that if he did not get into that mental state of fully knowing why he was there, he could not confidently step out on that stage and deliver his line correctly.

Party Presence

I thought deeply about the implications of this simple principle. I remembered immediately that when I went to a cocktail party “just to see who was there and mingle” I was much more anxious than when I went to that same party in order to meet my wife who was already there and who was going to introduce me to one of her friends.

I wondered whether my entry in the first situation was less noticeable than my entry in the second situation.

Did I have more presence when I knew what I was doing, had a purpose and a specific goal, in other words, knew why I was there?

Another Example: Honorary Presence

Life is a series of situations, some of which we can predict and some of which just overwhelm us. I was given an honorary degree at the Bled School of Management in Slovenia and knew that I was supposed to give some kind of talk after receiving the degree.

I had prepared a talk with PowerPoints and thought I was prepared, but when I arrived a day before the ceremony I discovered we were in a big hall, there would be many non-academics there, and giving my talk would be absolutely the wrong thing to do. I was quite anxious but also knew that just rewriting a short talk was out of the question.

I asked myself “why am I here?” What is this situation, what is expected of me and gradually realized the ritualized ceremonial nature of the event and that what would be expected of me was a few simple words of thanks and, perhaps a simple message that would “justify” the honor of being given the degree.

There were no scripted lines, but I knew that “some wise words” were expected from the honoree.

leaders communicate their values more by what they do not say and do -than by what they do say and do

I ran through a lot of stuff that had been in my talk and finally found something worth mentioning—how leaders communicate their values through their actions.

This was, however, a pretty pedestrian message and I knew I was there to say something more, something provocative, something new. But what?

It came to me as I was preparing to be called to the stage to receive my robe, my hood, and my degree, and it ended up being quite a satisfactory, powerful message. I felt I had presence and had something to say and was very grateful for having been able to “rise to the occasion.”

The message itself was important and relevant—that leaders communicate their values more by what they do not say and do than by what they do say and do.

Leaders did not notice that their failure to ask personal questions of their subordinates showed their lack of interest

Perhaps the most powerful example I observed over and over again was how leaders did not notice that their failure to ask personal questions of their subordinates showed their lack of interest in those subordinates and led to some of the disengagement that those same leaders later complained about.

I challenged the audience to think about this and said silently to myself, what a relief that I had discovered what I was there for and had not bored them with my long lecture.

The Benefits of Presence

Since that conversation with John, the actor, I have explored how widely applicable his simple principle is.

I have noticed, for example, that doctors in a teaching hospital who lecture to the residents about the case in front of the patient get much less good information than the doctor who believes they are there to form a relationship with the patient and concentrates on their conversation with the patient rather than with the residents.

I have noticed that managers who think they are there to help their subordinates get much better performance out of those subordinates than managers who think they are there to tell subordinates what to do.

‘Presence’ gets Across to Others

The form in which you present yourself gets across to others.

If you are not interested in them, they will sense this, as every therapist and consultant will confirm. Presence is about purpose and goals, not about personal style or personality.

If you know why you are there, if you have figured out your role in the total situation, if you know your lines, you will have presence.

It turns out to be as simple as that.

_____

We would like to thank Jonathan Løw, the editor of The GuruBook for kindly letting us publish this chapter: Edgar Schein – Knowing Why You are There.

You can find Jonathan Løw both on LinkedIn and on Facebook

180614